Research: A different kind of learning

Understanding the science behind movement and exercise is a foundation for University of Northern Iowa kinesiology students. In the classroom, clinical labs and through internships, students prepare for careers in personal training and fitness, strength and conditioning, youth sports or health professions such as physical or occupational therapy.

Understanding the science behind movement and exercise is a foundation for University of Northern Iowa kinesiology students. In the classroom, clinical labs and through internships, students prepare for careers in personal training and fitness, strength and conditioning, youth sports or health professions such as physical or occupational therapy.

Some of these College of Education students go one step further. They add to that knowledge as student research assistants while earning their undergraduate degree.

One question leads to another

Terence Moriarty, an assistant professor in kinesiology, initially completed his Ph.D. dissertation on exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation and how it helped improve function in cardiovascular disease patients. After subsequent research and publications, he says, “I have learned that aerobic exercise can have a tremendously positive impact upon aerobic capacity, cognition and brain oxygenation in diseased populations. This has huge implications for the importance of exercise in rehabilitation programs of this nature.”

While UNI is considered a comprehensive university focused primarily on education, research happens here as well. Kinesiology faculty, with their emphasis on human performance, regularly collaborate on studies and papers with colleagues here and across the country. For students, this means opportunity, including as an undergraduate student.

In research, answering one question often leads to another. Moriarty sought to extend his investigations through another project, this time with the assistance of UNI undergraduate students in movement and exercise science (MES).

Last spring, emails went out inviting students to an informational meeting about two potential research study projects. Five students were selected to join in with Moriarty’s project:

- Mason Palmer, Guttenberg, Iowa, class of spring 2021

- Ellie Spillane, Galena, Ill., class of spring 2021

- Allie Nietzel, Muscatine, Iowa, class of fall 2021

- Madi Young, Earlham, Iowa, class of spring 2022

- Mary Sutton, Marshalltown, Iowa, class of fall 2022

While Moriarty oversees the project, the students played a pivotal role in its development. “When we began reading about this topic back in January of this year, the students had a large say into what exact exercise intervention as well as what population of individuals that we would conduct this study in. They then helped write the IRB (Institutional Review Board) application and have been instrumental in learning the techniques of data collection ever since then. They have been so awesome to work with since the very beginning,” he says.

Sutton became involved her first semester as an MES major. She explains the student research role as: “to help design the experiment, conduct background research, collect data, analyze the data, and contribute to the research article.”

The group spent the spring reviewing current literature. Though not the most exciting part of the project, the five understood its purpose.

“During spring semester my classmates and I spent many hours finding and digging through case studies similar to our own. We would look for ideas for what we actually wanted our study to specifically be about as well as ideas as to what we may want to include in our study, or techniques we want to use,” explains Spillane.

Young found the process initially overwhelming and complicated, but became more comfortable over time. “Dr. T (Moriarty) and Fabio (Fontana) did a great job of answering my questions. During the first semester I learned a lot from both of them on how to read scientific writing,” she says. “As we progressed through the semester we started considering what aspects of other research projects we wanted to include in our own. Slowly we put the pieces of our own research project together.”

The project comes together

The group defined their project as a study of how exercise impacts cognitive performance and brain oxygenation--increasing the amount of oxygen delivered to the brain--in patients with depression. It will include a six-week multimodal exercise intervention, using various pieces of equipment to focus on agility, balance and brain training.

The group defined their project as a study of how exercise impacts cognitive performance and brain oxygenation--increasing the amount of oxygen delivered to the brain--in patients with depression. It will include a six-week multimodal exercise intervention, using various pieces of equipment to focus on agility, balance and brain training.

“We’re hoping to provide evidence that exercise increases brain oxygenation and cognitive skills and decreases depressive symptoms,” says Young.

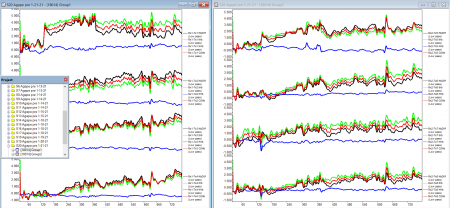

The literature review of the spring gave way to preparation for data collection this fall and development of the UNI IRB application. After review by the IRB, required for all proposals using human subjects, the group will begin actual testing with both healthy subjects and those suffering from depression in early 2021. Students will conduct studies with middle-aged and older subjects. The participants will wear a piece of equipment on their head called a functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) device. Optical sensors collect data via infrared light which help measure oxygenation and blood flow.

“For us, we are focusing on the prefrontal cortex during three different cognitive tasks. This gives us 10 data points every second, so as you can imagine the files from 10 minutes of data are very large,” Moriarty says. The last steps of the research cycle, students will collect and analyze the results and then develop recommendations for a paper for submission to professional journals.

The team just added a three-month follow-up trial to the research parameters. They’ll be testing the level of depression through questionnaire and interviews; aerobic capacity on a treadmill; and cognitive performance with brain oxygenation at pre-, post- and three months after initial testing.

“We feel this will very much enhance our understanding of how exercise can impact levels of depression, aerobic capacity, cognitive function and brain oxygenation for the long term, even after the intervention has finished,” says Moriarty.

When the group achieves final publication of the manuscript in a top-tier journal, Moriarty will consider the project done. He estimates that could be fall 2021 or early 2022. With varying graduation dates, not everyone will see the project through to the end. But most expect to assist as long as possible.

‘I’m graduating in May (2021), but I plan to stick around until August, or whenever all of our data is collected,” Palmer says.

The ebbs and flow of research

Through the past months, the students learned the ebbs and flow of a research process.

“Last semester was very monotonous and was the most difficult part so far. Lately we have been getting to practice with the fNIR brain reader and the cognitive apps so that has been a lot more interactive and fun,” says Spillane. “However, even though the first part may not have been super exciting, it was crucial to getting to where we are today. I am excited to actually record data and put it all together.”

“Last semester was very monotonous and was the most difficult part so far. Lately we have been getting to practice with the fNIR brain reader and the cognitive apps so that has been a lot more interactive and fun,” says Spillane. “However, even though the first part may not have been super exciting, it was crucial to getting to where we are today. I am excited to actually record data and put it all together.”

Nietzel, somewhat nervous as she joined the project, was surprised by her response. “I had never done something remotely close to this. I am not fond of writing papers or anything of that nature. However, I found that I actually really enjoy research. Testing and evaluating something that you're interested in definitely helps, but it has been fun to work with this group and go through it together,” she says.

Palmer had a similar reaction.

“When I think of doing a research project, I typically think of reading boring articles and meaningless meetings with our group. Rather, I was pleasantly surprised when we started researching. We were given lots of freedom with the process of figuring out what exactly we wanted to research and test,” says Palmer, who hails from Guttenberg, Iowa.

New perspectives, future options

Whether or not research is part of their future careers, these UNI students already see benefits to participating in the study.

For Young and Sutton, this experience prepares them for further research opportunities in graduate school for physical therapy.

“This is a really neat project for me especially, since I'm a movement and exercise science and psychology double major,” says Sutton. “I've gotten to see how both of my interests can be combined and hopefully lead to results that can help people. It has helped in the classroom setting as well by familiarizing me with the language used in research papers.”

“I've learned a lot about the field of kinesiology in general and the research process. It's taught me to think critically and to think outside of the box,” adds Young. “My professors reference lots of studies that have been done in the past and how research affects every field within the realm of exercise science. It's helpful to understand the process of research when it's being referenced.”

Nietzel plans on practicing occupational therapy, but this experience has opened her up to research, given the right group and topic. “If you would have asked me about research before participating, I would have laughed and said no. After going through the process and learning a lot from it, I am not opposed to doing another research project,” she says. “It has also been so much fun to get to know this group and build deeper connections with Fabio and Moriarty as they truly are some of the most helpful, knowledgeable and enjoyable faculty members I have met at UNI.”

Spillane, also a pre-OT student, sees the potential for research, but finds the experience itself enriching.

“Since we are a small group, we get to be very hands on and each of us is responsible for everything that happens. We are held accountable for getting what we need done completed, because there is no ‘I'll take a zero on this homework,’” says Spillane. “Every assignment is crucial to keeping us moving forward. We are lucky to be so heavily involved with every step of the process. It makes every success extremely rewarding.”

She adds: “If there was an opportunity to conduct research involving adaptive equipment or recovery rates or something of the sort, I would love to take part. My experience at UNI would definitely prove helpful.”

Palmer, who’s leaning toward a future in strength and conditioning, is uncertain whether more research is part of that path. Nevertheless, he says, “I’m extremely glad that I got to conduct this research at UNI. The experience I gained while working on this project will no doubt help me in my career, no matter what that may be.”

The value of a research experience

Moriarity has specific goals in exposing these undergraduates to research.

“I hope that they are able to appreciate the volume of work that goes into one research project, especially an intervention or longitudinal one like this. In addition, they should be knowledgeable--almost experts--about our topic area, understand the IRB process, be fully comfortable with operating the equipment and interacting with participants in the study. Being able to interact and converse with participants is something that is really important as they progress through their own careers,” he says.

These five MES students are part of something special, Moriarty says.

“It’s important to note that these opportunities are very rare at the undergraduate level. I did my undergraduate in Ireland and was fortunate enough to complete my own project in golfers during my senior year, but there is no other school in the U.S. that I have seen anything similar. This experience will set these students apart when moving on to future careers and graduate school,” he says.

“If students can walk away with the ability to fully understand and appreciate the research process as well as gain some credit hours and have fun, then I think they have benefited hugely,” he adds. “We see the ‘real’ student outside the classroom and during the undergraduate research experience, which is a real joy.”

Palmer spoke for all the students in acknowledging the impact of their work.

“Being part of this research group has more of a 'real life' feel to it. It does not seem like I have to be doing this for a grade. Instead, I feel like an important factor in gathering this information and being able to apply it to real-life situations,” says Palmer. “For me, this has added to my classroom learning by getting to put my hands on a project that will potentially have an effect on how people will consider using exercise as a method of treating or lowering depression in middle-to-older-aged people.”