Derecho? Pandemic? Not to Worry...

Student teaching coordinator Leasha Henriksen normally looks forward to a face-to-face celebratory orientation and kick-off to student teaching prior to the field experience she oversees each semester for the UNI Teacher Education Program.

Student teaching coordinator Leasha Henriksen normally looks forward to a face-to-face celebratory orientation and kick-off to student teaching prior to the field experience she oversees each semester for the UNI Teacher Education Program.

Instead, on Monday, August 10, 2020, she was sitting at her kitchen table at her house near Alburnett, Iowa, finishing an orientation video on her laptop. “I had communicated to my students that starting Monday, I would release one asynchronous orientation module; a second on the 11th, and then we’d gather for a Zoom and Q&A,” she says.

Then, her phone rang. It was her mother in New Hartford, Iowa. “You have terrible weather coming your way,” she said.

Henriksen glanced out the window and said, “It looks fine.” Shortly after hanging up, her husband Josh, the principal at Alburnett Elementary School texted: “Get to the basement.”

A neighbor next called over, concerned. “Then, just like that -- boom! -- it was like a curtain dropped, it turned black and it started,” says Henriksen.

“It” was a historic storm called a derecho, a combination of rain and 100+ mile-per-hour straight winds that roared through central Iowa that day, turning an already unusual summer upside down once again for many in its path.

Henriksen turned on the radio, which almost immediately lost power. The wind picked up, bending small trees to the ground in the young subdivision north of Cedar Rapids and blowing lawn furniture everywhere. She scurried to the basement. “I could hear the wind, and then all of a sudden I heard a waterfall, turned around and saw water pouring out of the heat runs. You could barely see through the basement window -- the rain was so heavy -- and you could see black things flying by. This was the real deal,” she recalls.

Eventually, the wind died down, she headed back upstairs and looked out to see shingles and debris everywhere and a backyard trampoline lying mangled in a neighbor’s garage. She had a yard, a house and a neighborhood to clean up, no power -- and about 30 students still on the eve of their student teacher orientation and placement. Did they have somewhere to go?

Picking up the pieces

“I was supposed to meet a group of my student teachers that afternoon to pass out their masks and student teaching face shields. We were going to meet in a Target parking lot. But there were power lines all down, I couldn't even get out of Alburnett,” Henriksen says.

“I was supposed to meet a group of my student teachers that afternoon to pass out their masks and student teaching face shields. We were going to meet in a Target parking lot. But there were power lines all down, I couldn't even get out of Alburnett,” Henriksen says.

She did manage to track down working cellphone service at a neighbor’s later that day, getting emails out to her students -- hoping she would connect, and reassuring them to “hold tight” as everyone figured out next steps. With road blockages and limited communication, she did not fully realize the scope of the storm’s impact at first. “I never thought we’d be talking 12 days without power,” she says.

Nevertheless, that Thursday she met up with about one-third of her students in a coffee shop in North Liberty. “They just wanted reassurance. I said we need to learn more from the state and the Department of Education. We’ll figure it out and deal with orientation next week,” she says. Thanks to her persistence and welcoming and supportive school district partners, by August 27 all her students were in a classroom or in professional development.

As the student teaching coordinator for the Cedar Rapids Center, the UNI College of Education instructor coordinates placements ranging from grade school through high school across multiple area districts. Cedar Rapids, Linn Mar and the Marion school districts were the hardest hit, with building damage to middle and high schools also creating a ripple effect in terms of classroom availability.

As the state and the schools figured out their next steps, Henriksen’s approach was triple-pronged -- reassuring her students and her school partners while reaching out to other schools for assistance.

“I just told my CR, Linn Mar and Marion students--we've just hit pause, don't worry, we’ll figure this out,” she says. Her students now fell into three cohorts: those greatly impacted and needing new placements; those less impacted, but needing some adjustments; and those in a few districts which escaped the storm’s wrath. About 10 students would need new placements.

“We had great Cedar Rapids teachers and partners who were willing to continue to do whatever they could--but we also wanted to get our students into the classroom, so I started placing them,” she says. “I emailed Cedar Rapids teachers right away. I just let them know...this is not your burden, you have to take care of your families and homes.”

She then turned to contacts in neighboring districts, like College Community, HLV and Alburnett for help. In one case, it took just one email to HLV principal Cory Lahndorf, who responded right away: “Yes, he's welcome here. Here is my teacher contact information.” Teachers at College Community offered to take students for the first seven-week session instead of the later session, giving Henriksen more flexibility to adjust.

“We have some amazing partner schools,” she says. “Those mentor teachers were willing in midstream to say yes, bring them over. Some were already in school. They were able to help the profession and their neighbors. It was just wonderful.”

Returning to classrooms

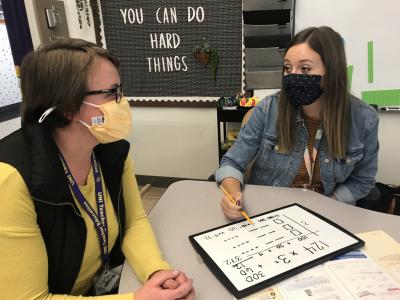

Bailey Wright (‘16, elementary education) is a special education teacher at Alburnett Elementary who unexpectedly stepped into the role of cooperating teacher this fall. She, too, sat out the storm in the basement.

Bailey Wright (‘16, elementary education) is a special education teacher at Alburnett Elementary who unexpectedly stepped into the role of cooperating teacher this fall. She, too, sat out the storm in the basement.

“The wind sounded stronger than anything I had ever heard....When I went back upstairs, the power was out, my phone didn’t work, and it was chaos outside.” Insulation covered the ground, one tree was completely missing and power lines were snapped. “It was hard not being able to call family members to check in and know what was going on with other colleagues and loved ones in the area,” she says.

She and other neighbors pitched in to help, running over to a nearby apartment complex with buckets and totes to help with a flooding basement in those first hours. Later in the week, they grilled food outside for elderly neighbors. Generators hummed for 10 days straight. And then, two days before she thought school was starting, Wright received a request to add UNI student teacher Chloe Pflughaupt to her class.

“While it was not in my plans, I knew that with her UNI training, she would be a great addition to our classroom. I also knew that with trying to limit group sizes due to the virus, it would be helpful to have more hands on deck to work with students. Our start date was pushed back one week due to the derecho, so we had a little more time to prepare for students,” she says.

Steve Vanderpol, student teaching coordinator for the Marshalltown Center, did not need to move students after the wind swept through central Iowa. However, some student teachers encountered shorter placements or more time working with cooperating teachers and building level colleagues as district schedules adjusted to a return to school, post-derecho and in a continuing pandemic.

“No one got hurt and everyone is slowly recovering, which we are all thankful for,” he says. “The other things our student teachers experienced will make a difference in their classrooms of the future.”

Wright says her student teacher “got a very real look into teaching and the flexibility we must have as teachers. Chloe got involved in the classroom quickly to help meet student needs and support the wide array of situations we were challenged with. We were working with students that had experienced hardships with parents losing their jobs, family members experiencing the coronavirus and students displaced and living in hotels or with family due to the derecho.

“She did a fantastic job connecting with students and also planning engaging instruction. It was important for us both to reflect often on our teaching and students and be ready to change our plans as needed,” Wright says.

Lyn Countryman, head of the college's Department of Teaching, says a strong network supporting field experience at all levels made it easier for UNI to adjust to this year’s unprecedented challenges.

“Part of the reason why this has worked so well is because our coordinators across the breadth of the field experience, from Level 1 to student teaching, have developed personal relationships with teachers and districts,” she says. “It’s the personal quality assurance and personal relationships built over time -- because we have full-time faculty -- that allow us to team with the public schools to make these placements.”

Despite derecho, student teachers carry on

When a historic derecho struck the Cedar Rapids, Iowa, area on August 10, Annie Efting found herself in the basement of the home where she served as nanny to seven children.

nanny to seven children.

“We were in a room with no windows, thankfully, so no kids knew exactly how bad the storm truly was,” says Efting, a University of Northern Iowa senior who was about to begin orientation for student teaching in the Cedar Rapids school district. “Once we got the okay that it was safe to go upstairs, I was in a state of shock. I couldn’t even contact the rest of my family in Cedar Rapids because no one had cell phone service. It was nerve wracking for a couple of hours until I could get home!”

Chloe Pflughaupt was another student preparing for student teaching while living in Palo with her family over the summer. That day, though, she was in Cedar Rapids where she and her boyfriend were planning to go golfing. Then her mom called, telling her about the storm.

“When it hit, we (Chloe, her boyfriend and his grandmother) were all upstairs watching it roll in,” she recalls, surprised by the unexpected storm. “The wind quickly picked up and trees started blowing over--one of the trees actually hit a kitchen window and broke it in. At that point, we went downstairs to wait it out from a safer location.”

After the wind slowed, they emerged from the basement to find multiple trees down in the neighborhood, including two large trees that buried her car in the driveway. Read the rest of the story.

In her own words: Bailey Wright

Much has been written about the changing experience of UNI College of Education students and faculty in university coursework, classrooms and field experience. We asked alumna Bailey Wright (who is currently working on her principalship M.A.E. through the UNI College of Education) to describe her experience in a K-12 classroom these past months.

“Once we shut down in the spring, our main goal shifted from academics to safety. We were checking in on families, ensuring they had food, and trying to provide some sense of normalcy for our students. We did many Zoom lessons centered around math and reading, but also some just to talk as a class, have talent shows, show and tell, etc.

“Once we shut down in the spring, our main goal shifted from academics to safety. We were checking in on families, ensuring they had food, and trying to provide some sense of normalcy for our students. We did many Zoom lessons centered around math and reading, but also some just to talk as a class, have talent shows, show and tell, etc.

“Over the summer, I placed a lot of my focus on the possibility of being in school or virtual, and how I could be prepared for either. Some students were in every Zoom class and completed every activity, and some we never heard from despite our endless attempts. It was important for me to plan for that scenario over the summer and think about where I could build in the missed standards to the current grade level standards.

“We did not know we were fully back in person until the end of July. We came back fully in person, with masks strongly recommended. We had no shortage of hanging shower curtains, plexiglass and spaced desks, which made the learning atmosphere quite different for students.

“Now more than ever, I am learning to check in with students emotionally first and acknowledge the COVID fatigue we are all feeling. Academics remain a priority, and our students' mental health does as well. The kids have adapted incredibly well to our new normal this year, and I have been focused on meeting the kids where they are and embracing the hardship we are all in.

“During my time at UNI, I learned a great deal about differentiating instruction, which is what this fall has been all about. Now more than ever, we have students at different levels, and I have leaned on my background in co-teaching and inclusion to meet the needs of students without just pulling them out of the classroom.

“I also have relied on my (classroom) management background in recognizing student behavior as communication and helping the whole child. In these times of stress, students have different ways of communicating that to us, so it has been important for me to be on alert and notice changes in behavior.”